This year Catholics enter the most important week of their religious calendar with a new pope, and if you’re like many of my colleagues, this doesn’t mean much to you. I don’t see much writing about religion among the ecologically-minded, perhaps because many are not very religious themselves, or perhaps they are avoiding that most delicate of subjects. I want to make a case, though, that you should care – perhaps about the new pope, and definitely about religion in general – as you make plans for the future.

As a bit of

background, you might have heard that the last pope took the unusual step of

resigning a few weeks ago; popes usually hold the office until they die, and

the last one to willingly step down was more than 700 years ago. The new pope,

Francis I, is all kinds of other firsts – the first from the Western Hemisphere,

the first from the Southern Hemisphere, the first from outside Europe in 1,300

years, the first from the church’s 500-year-old Jesuit order, and the first to

be visited on their inauguration by the head of the Eastern Orthodox Church for

almost a thousand years. Unlike some of his predecessors he has been deeply

critical of the global financial system that has left so many Third-World

countries poor and indebted, and he has impressed observers with many small

gestures toward simplicity.

He now heads a

church devastated by massive sexual abuse scandals in several countries, and

will have little credibility unless he starts sacking people left and right for

covering up those horrific crimes. They were just the most recent blows,

however, to an already weakened religious empire.

Most people know something

about our clergy and rituals from mass media, for when Central Casting needs

someone to be demonically possessed or Whoopi Goldberg to wear a disguise, the

Hawaiian shirts of feel-good mega-church pastors just don’t cut it. We

represent all things arcane and traditional in Hollywood pop culture, yet that

same culture has made those traditions difficult to maintain. Our deliberately

paced rituals were not made for a world of ubiquitous iDistractions, or our

austere teachings for a world with the comforts and sexual freedom of Egyptian

pharaohs.

Recent popes made

some small concessions to a rapidly changing world – allowing the Mass to be

said in local languages rather than in Latin, for example – but they often just

alienated traditionalists, while not making the meaty concessions that many

modern Catholics want. If anything the Church has responded to the modern world

by forbidding more and more of it; formally opposing abortion in 1869, and

contraception from 1930. Pulled and pushed from many directions, a growing

number of the world’s billion-or-so Catholics silently question how many catechism

points they can disagree with before they need to start calling themselves

something else.

Today the world’s

largest denomination of the world’s largest religion is undergoing its own kind

of slow collapse – not vanishing, but shrinking rapidly in the First World. To

use one small but typical statistic, the seminary (school for future priests)

near where we live in Ireland ordained 558 priests in 1963 -- a mere 12 entered

last year. Catholics in the USA are melting away from the Church en masse,

their numbers only partly obscured by a flood of Hispanic immigrants. When I

returned to my hometown last year, where I attended junior seminary myself

once, I discovered almost all the Catholic schools had closed, and my old

church had taken out its cry room for mothers with babies – there hadn’t been

any in a long time.

Some former

Catholics I know have become militant atheists of the new breed, who embrace

nihilism not with mourning, as Nietzsche or Camus did, but with glee. Others

have been caught in the gravitational pull of the USA’s fundamentalist

movement, which has spent the last few decades building an extraordinary media

empire and absorbing more and more American Christians into its cultural

bubble.

Perhaps the

oldest surviving organisation on the planet, one that survived the rise and

fall of several empires and centuries of hardship, is failing in an age of overabundance,

most in the most abundant parts of the world. It needs to decide what kind of

church it wants to be as we pass into the next and particularly difficult era

ahead. So for Catholics, this is kind of a big deal.

I know, the

Church has a lot of shameful history – so does my native USA, or Britain, or

France, any other country or organization with a bit of history behind it.

Point to the Inquisition and I’ll point to one of your group’s original sins,

because there will be some. In each case, though, the past doesn’t necessarily

represent the present, nor do the shameful parts negate the brilliant parts,

nor do some decisions by a government represent all actions of a people. I’m embarrassed by some of my countrymen but

not ashamed of my country; it’s home to me, and I’m proud of its better angels.

Perhaps you have your own example.

To extend the

metaphor, Francis is being greeted by Catholics as Obama was in the USA. He’s a

demographic first that seems to reconcile a painful history, made in a time of

crisis and potential. As with Obama, however, people are projecting all kinds

of hopes and fantasies upon him, and some will inevitably be disappointed when

he does not walk on water.

As I said, if you’re

not religious, none of this seems very important compared to the years of

global crisis we anticipate. We all know that our species is burning away the world’s

supply of fossil fuels upon which our economy depends, and disrupting the

weather in the process. We know that the living systems that keep the Earth

running are seeing one of their periodic mass extinctions – not an asteroid or

super-volcano this time, but a single ape species – and we know that past

crises didn’t heal on a human timescale. I’m right there with you.

As I said, if you’re

not religious, none of this seems very important compared to the years of

global crisis we anticipate. We all know that our species is burning away the world’s

supply of fossil fuels upon which our economy depends, and disrupting the

weather in the process. We know that the living systems that keep the Earth

running are seeing one of their periodic mass extinctions – not an asteroid or

super-volcano this time, but a single ape species – and we know that past

crises didn’t heal on a human timescale. I’m right there with you.

Think about this,

though: What if you are trying to work against these trends, and rally others

to your cause? What if you are trying to build communities, or change the way

people vote, or organise protests? What if you want to assemble communities in

the country to become self-sufficient? And what if, hypothetically, your allies

hail disproportionately from specific subcultures – tech-savvy,

upper-class,

coastal, countercultural, socially libertine and irreligious?

We tend to live

in bubbles of people like us, and while social media has made it easy for

people to have geographically disparate “communities,” I find that most people

still communicate mainly with others of the same generation, education,

religious and political attitudes. If no one you know goes to church, for

example, you might forget that 40 per cent of Americans do, and forget to

factor that into your community-building.

Not all people

who don’t talk about their faith are nihilists, of course – some just walk

rather than talk, and I wish more people did. I’m not a fan of the current

fashion in the USA, where oversharing about faith became popular around the

same time as oversharing about sex and other private matters. If you want to

deal with others in creating a future, however, you must be prepared to deal

with the fact that most people believe in something, and that it will not and

should not remain tucked away under a basket.

For one thing,

religion often deals with the most basic assumptions of one’s life -- the visceral

and magical attitudes that underlie our political and religious affiliations.

Since we so often refuse to even examine, much less talk about, such attitudes,

we often engage in culture wars without talking about the thing we’re really talking

about. When an acquaintance of mine said he disagreed with evolution, for

example, I politely asked probing questions, and with each answer I was more

confused than before. He was intelligent and well-educated, and each sentence

was cogent and eloquent – but I didn’t see their relationship to the subject or

each other.

The problem was

that he began from the assumption that evolution was what some atheists think

it is, an anti-religion religion that evangelises a meaningless existence. I,

however, was referring to the evolution that scientists study -- the way that

living things change over time. (I know Richard Dawkins falls into both camps,

but most scientists I know don’t.) You could replace the word “evolution” with

“existentialism” and his answers would be much the same: Evolution can’t

explain everything. Evolution doesn’t comfort you in grief. Evolution won’t

save you when you die.

You could replace

“evolution” with “digestion” or “precipitation,” however, and they would have

made about as much sense to me. Does digestion explain everything? Does

precipitation comfort us in grief? Or, if we’re talking more about the history

than the process, replace the word with any historical event: does the Moon

landing address the problem of evil? Can the Civil War explain everything?

Religious beliefs

include, or are influenced by, such baseline assumptions, and much of their

jargon exists to separate people inside the group from outside. When someone

asks me if I’ve accepted Jesus as my “personal saviour,” or insists they are

“just Christian” of no particular type, it gives me a clear idea what type of

Christian they are.

Neglecting such a

powerful force in our lives, or its absence, prevents us from seeing their

effect on the political and social landscape – and how they are affected by it.

Take, as an example, the early 20th-century debate between

pre-millennials and post-millennials – which has nothing to do with people born

around the year 2000, and everything to do with how we think of the future. To

oversimplify, post-millennials believe humans could and should make the world

suitable for Christ before he returns, whether it be the Puritans’ idea of

suitable or Martin Luther King’s. Either way they tend to be optimistic and

ambitious in creating social change – in King’s words, “the arc of the universe

… bends toward justice.”

Pre-millennials,

on the other hand, believe that the world will get worse and worse before the

Second Coming, and their visions lean toward fatalistic, Zombie Apocalypse

territory – when you hear about “The Tribulation” and “The Rapture,” it’s

probably from a pre-millennial.

It might not be a

coincidence that the two seem to rise and fall with the fortunes of a country.

In the early 19th century, as the USA headed closer to civil war,

pre-millennial movements like the Millerites spread across the then-frontier,

hailing the end of the world until the “Great Disappointment” of 1844. As the

Millerites fragmented into many other groups – that’s where Seventh-Day

Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses come from – post-millennialism seemed to

gain steam, and their idealistic movements helped abolish slavery, invent

labour rights and give women the vote.

As the USA became

the dominant global power, post-millennial churches remained powerful through

the civil rights movement. Then, as the country passed its domestic oil peak

and the public grew aware of ecological dangers ahead, an ecological-sounding

book called The Late Great Planet Earth

became a runaway hit – it’s often claimed to be the best-selling book of the

decade. That book inspired a growing pre-millennial movement among the young

and countercultural, which evolved into the nationalistic and somewhat paranoid

fundamentalism so influential in the USA now.

As the USA became

the dominant global power, post-millennial churches remained powerful through

the civil rights movement. Then, as the country passed its domestic oil peak

and the public grew aware of ecological dangers ahead, an ecological-sounding

book called The Late Great Planet Earth

became a runaway hit – it’s often claimed to be the best-selling book of the

decade. That book inspired a growing pre-millennial movement among the young

and countercultural, which evolved into the nationalistic and somewhat paranoid

fundamentalism so influential in the USA now.

You’ll notice,

though, that both of these strains of Christianity pretty well parallel the two

visions of the future popular in the fossil-fuel era. In the mid-20th

century, when Westerners saw rapid technological and social progress, the

gospel of progress affected not just religion, but politics and science.

Evolution was reframed as the ascent of Man, my country’s expansion reframed as

Manifest Destiny, history as the March of Progress. When my country’s tables

turned in the 1970s, not only did the religion get apocalyptic, but politics

and popular culture did too.

Whether the

religion led or followed the other trends is difficult to say, and of course

not everything falls into these neat categories – apocalyptic thinking was

around long before the first oil well – but their popularity does seem to rise

and fall with energy inputs. If this pattern holds, we might expect to see

pre-millennialism – what I’m calling “fundamentalism” - continue to be one of

the few things that boom as fossil fuels decline.

That could be

very bad news for the rest of us if they persist in attacking basic science

education in my own country, because of their aforementioned ideas about

evolution. People can have their own opinions about gay marriage or abortion –

there are good people on all sides of these issues, and we can sort out our

differences democratically. We can also have respectful differences about our

faith in the unproven. We do not, however, have to respect someone’s faith in

the disproven, and a generation without science education is the last thing we

need as we enter an ecological crisis.

On the other

hand, I’m throwing around terms like fundamentalist, evangelical and

mega-church as though they were interchangeable, and of course there are many

divisions and nuances. I know many fundamentalists who would make bitter

flame-war enemies online but great neighbours in a real-world crisis. I also

know others whose faith has inspired them to adopt a more traditional way of

life – and in doing so pave the way for the rest of us. Also, many groups settle

down over time, or we soften toward them; we don’t think of the “Salvation

Army” as being a genuine army, say, getting into shooting wars with gangs, but

once they were and did.

None of those

religious groups, though, completely abandoned their belief in progress, and

these days most people across the political and religious map tend to celebrate

progress in some area – whether it be newly broken cultural taboos or newly

vaulted Dow numbers. Most people I know, of any political or religious group,

feel perfectly comfortable questioning their opponents’ version of progress,

but respond indignantly to any questioning of their own version.

Of course we have

progressed -- few humans have experienced our level of comfort and freedom, our

health or literacy. We live in an age when humans live eight decades, and with

a few touches of a finger can connect to the wisdom of the world. Yet most of

those changes exist because of fossil fuels and the technology they allow; that

cheap-energy window appears like a needle along the timeline of humanity, and

as we pass over one peak after another we need to think about what parts of

progress are objectively right and necessary for our descendants. Nor has the

freedom to choose every aspect of our lives necessarily made us happier, as far

as such things can be measured, than people who did not have such choices.

The myth of

progress also doesn’t allow us to say no. It assumes that if a little of

something was a relief to oppressed or impoverished ancestors -- wealth,

choices, entertainment, anything – that we have to keep following that trend

forever. It doesn’t allow us to stand astride history yelling “Stop!” It

doesn’t let us say when we’ve had enough, even when the enough we have is

temporary. That’s what

religions are supposed to do.

Religions done

rightly – which usually means traditions that pre-date the cheap energy window

–go against today’s left and right alike, and violate every value we learned

from generations of stump speeches, motivational seminars and Disney movies. They

don’t tell you that you should always follow your heart, or that you are

destined for greatness, or have a right to choose whatever path you

Religions done

rightly – which usually means traditions that pre-date the cheap energy window

–go against today’s left and right alike, and violate every value we learned

from generations of stump speeches, motivational seminars and Disney movies. They

don’t tell you that you should always follow your heart, or that you are

destined for greatness, or have a right to choose whatever path you

want, or

that everything will work out all right in the end.

It tells you that

you are frail and flawed, here only briefly, that your problems are not very

different than everyone else’s, and that we are all in this together. They give

our mayfly lives an umbilical cord to eternity – and even if you don’t believe

that happens on a spiritual level, the tradition does in this world. There

aren’t many institutions that allow us to cite the centuries of the second

paragraph, or whose still-standing monasteries kept learning alive through the

end of the Roman Empire.

Now another

empire is declining – the USA specifically, and the globalised consumer culture

in general. In Walter Miller’s novel A

Canticle for Liebowitz, a group of Catholic monks preserve the bits of

Western Civilisation after a nuclear war, sometimes without understanding it,

until the world is ready for it again. The real collapse will probably not be

as dramatic as a thermonuclear exchange that seemed so imminent when it was

written five decades ago, of course. It will likely be more of the small

crashes and crises we have seen in the last decade, giving us a bit of space to

do something like the monks of the novel – or the real ones fifteen centuries

ago, whose ruins dot the fields around us.

So let’s say you

want to help your descendants transition into as humane and civilised an

existence as possible, even though you won’t be around to see it. You want to

teach children to live a more sustainable life of less consumption and energy

use, even when a million distractions around them tell them to do otherwise. To

live out this vow of poverty you might need to encourage them to withdraw from

the world, as St. Benedict did long ago, and build a community of people who

believe the same. You will need to inculcate strict code of restraint in your

congregation, and teach a set of rituals that will help people succeed at this

new life.

There – you’ve just become religious. Whatever your opinions

about the supernatural, you have a set of traditions, rituals and values that

sustain you through hardship. There are many

traditions you can draw from, of course – I have mine.

Perhaps you have

your own example.

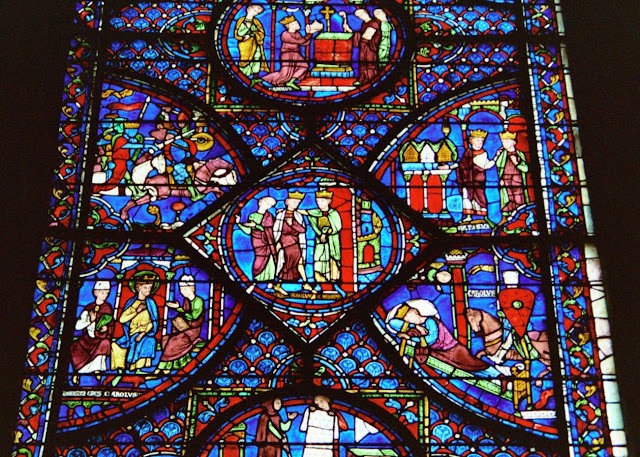

Top photo: Window of Chartres, courtesy of Wikicommons.

Second photo: Priests emerging from the seminary at Maynooth near our home.

Third photo: Priest blessing a gardai (policeman) in Ireland. Both these photos seem to be from around the 1930s and are used with permission from Irishhistorylinks.com.

Fourth photo: The graveyard at Glendalough, a monastery built in the 500s.

Final photo: The stream at Glendalough.

3 comments:

Great essay. You've articulated something about community and ritual and belief my late Husband and I talked about years ago in the mid-70s. Our dream was to build a sustainable community, based on shared beliefs, and unplugged from the consumer society which we believed would begin to implode in our lifetime. It's now a shared discussion with our adult children, and my new Husband...and friends of more than just our generation in our local Eastern Orthodox Church.

Perhaps God, however one defines Him, is moving His people (and aren't we all His people, created in His image?) is moving us to look deeper into the world around us and go back to the future to sustain each other and our families; preferring others needs to our own, and all that...

Thanks, Aoibhinngrainne. I'd love to see such communities, religious or otherwise, dot the landscape around us -- I wish you the best with your dream. Where are you located, by the way?

Such a good essay. Thank you.

(signed)

Toomas (Tom) Karmo (in Ontario)

www dot metascientia dot com

Post a Comment